Unknown Women Scientists Who Changed Your Understanding Of Reality

How many female scientists can you name that aren’t Marie Curie? Even today, the stigma about women in science persists, but each of the women in this list have directly contributed to the lexicon of modern life.

1. Ada King, Countess of Lovelace

The only legitimate child of the infamously promiscuous Lord Byron, Ada King was raised by her mother, Anne, after her father abandoned them when Ada was only a month old. Anne wanted to quell any potential bohemian characteristics that Ada might have inherited from her poet father, and thus engaged her daughter in heavy logical and mathematical studies. Ada’s talents were recognized early on, and Ada became a close colleague of Charles Babbage after he learned of her talents from her famous tutors.

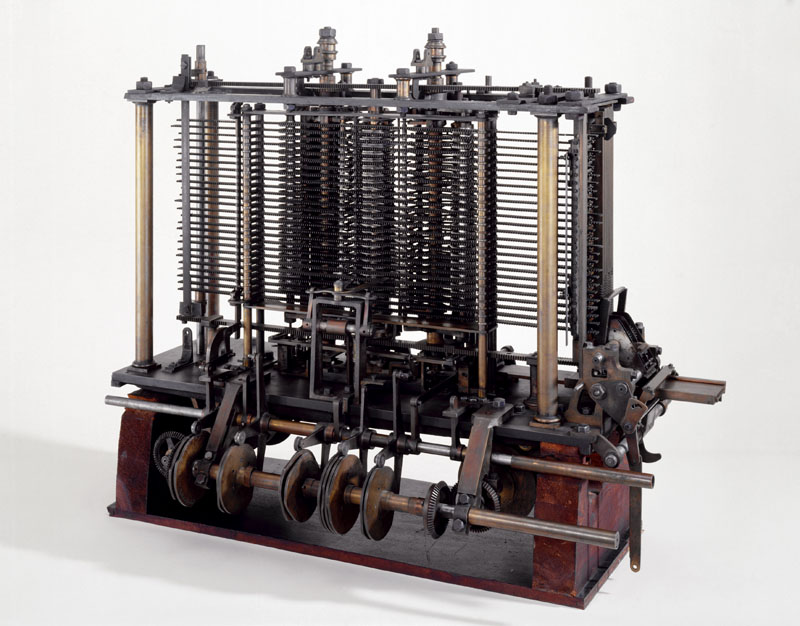

Punch cards and computational machines had been around since the turn of the 19th century, but by 1842, they were still clunky, specifically arithmetical computers. Babbage had worked on computation machines called difference engines, and had just proposed a new engine, called the Analytical Engine. Lovelace recognized the potential of Babbage’s engine went beyond simple or even complex mathematics, and devoted herself to furthering Babbage’s work. While translating and extrapolating on an Italian article about the analytical engine, she wrote the first algorithms that would be considered a computer program.

It would be over a century before anyone recognized her notes for what they were, and Lovelace for what she was: the world’s first computer programmer. In 1953, as modern computer science was still in its larval stages, Lovelace’s notes were republished as an homage to her contributions and to the progress made in the field.

2. Emmy Noether

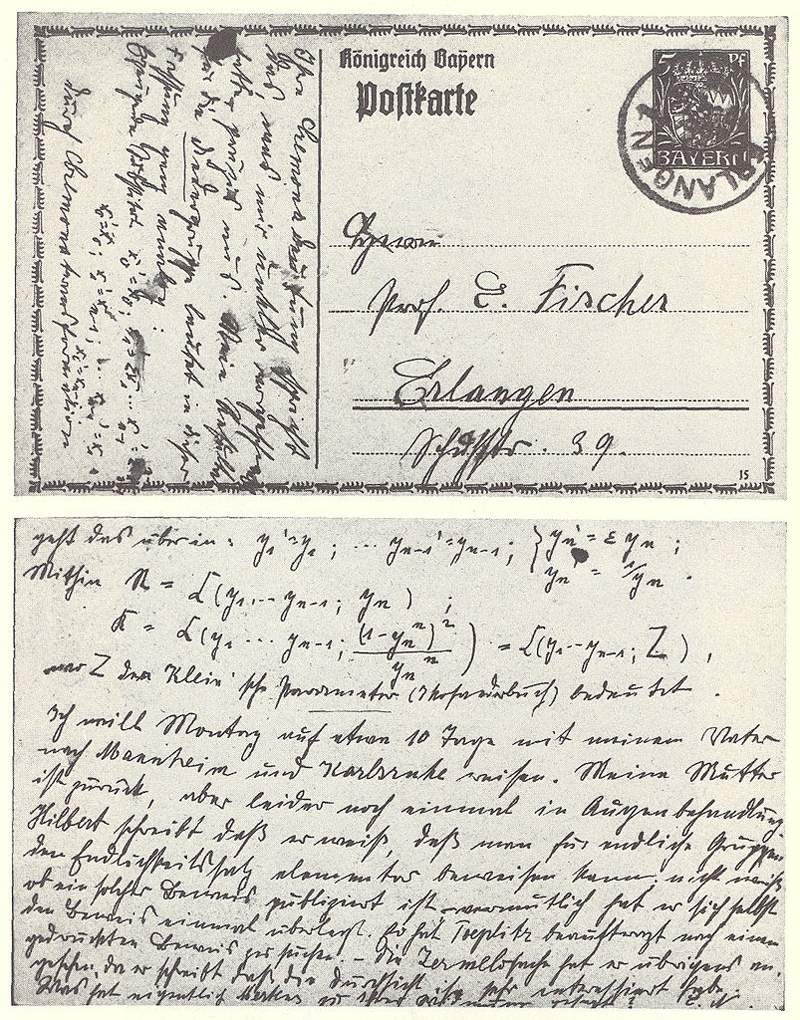

It is hard to explain Emmy Noether’s importance within the body of her work because in order to truly grasp how revolutionary she was, you would likely require a few mathematics PhDs. Emmy Noether is cited by Einstein and his contemporaries as the Athena of math, and a woman without whom modern mathematics and its teaching would be fundamentally different.

Noether is responsible for abstract algebra. She completely rewrote the books on so many mathematical concepts that the adjective Noetherian is found in several different concentrations within mathematics. Her theorem, aptly dubbed “Noether’s Theorem,” yields fundamental laws such as the conservation of linear momentum and the conservation of energy. Even today, Noether’s work is used in the study of black holes, objects that were still science fiction for decades after her death.

Noether is not simply the mother of modern mathematics because she was a prolific revolutionary. She was the Giving Tree of mathematicians, allowing scholars to use her work without credit. Because of her intellectual generosity, she is honorarily listed as a coauthor of contemporary math articles—often in fields that have only a cursory affiliation with her work. A dark side Lunar crater is named for her, as well as an asteroid in the Solar System’s main belt.

3. Mary Anning

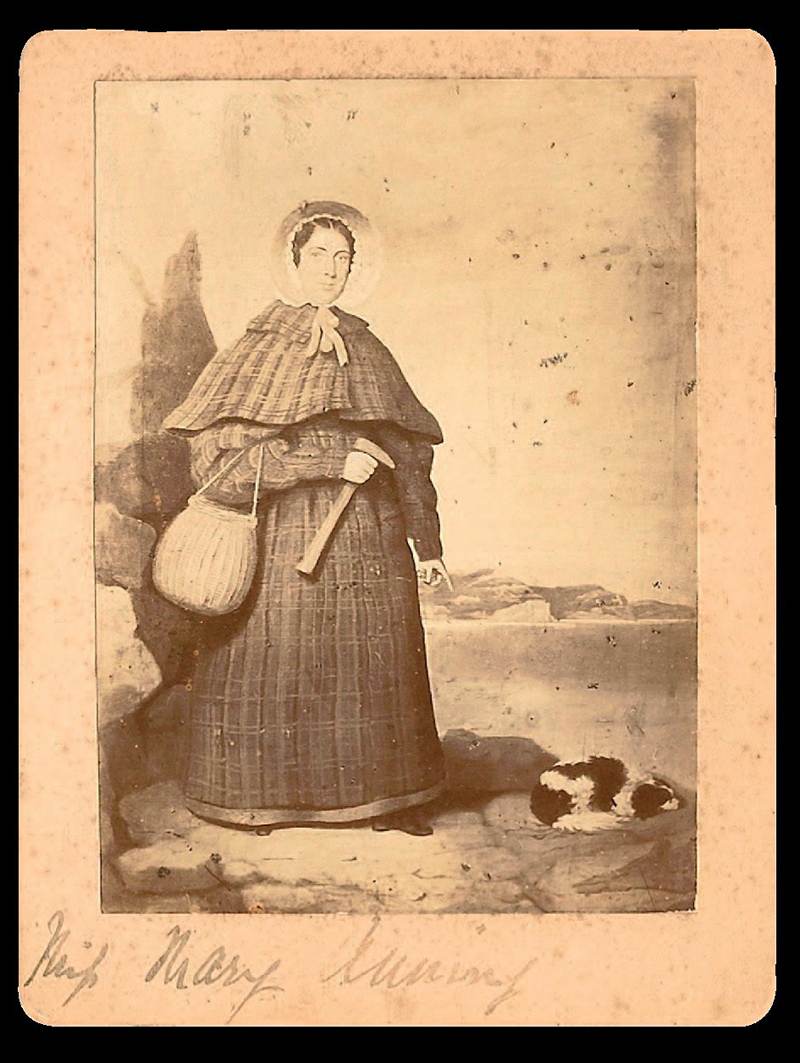

Mary Anning was born into a British working-class family in 1799. She was named for her late sister who died in a fire, and was herself the sole survivor of a freak lightning strike that killed three women who were doting over her. Her father was a carpenter who mined fossils in his free time to sell to tourists, and he often took his children with him on his searches. Though it was expected of her to take a peasant’s vocation, she was inspired by her Congregationalist minister’s fascination with geology and decided to make a career out of fossil digging.

Anning made a series of revolutionary discoveries in the early 19th century, excavating huge skeletal sections of ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs between 1809 and 1829. Fossils of these ancient dinosaurs had been uncovered before, but a consensus on what they really were had never been reached, since Biblical literalism was widespread–even among educated elites. The claims of “extinction” from Anning and her contemporaries were as offensive as they were radical. Nevertheless, Anning was able to build a great reputation and career out of her fossil digging, and became so famous for her marine fossils that it is believed the tongue-twister “She sells seashells…” was written about her. She found the first Ichthyosaur when she was only 12, digging up the rest of the skeleton after her brother found a skull nearly as long as she was tall.

Anning’s contributions effectively settled the argument of extinction, and became the founding ideas behind the burgeoning field of paleontology. Her status as a the poor daughter of a heretical family was a huge impediment to her recognition in the scientific community, and though she was the go-to source for rare and complete fossils, the geologists who published reports about Anning’s discoveries never mentioned her involvement. Since her death, she has had several species named for her in homage to her importance in the paleontological paradigm shift.

4. Lise Meitner

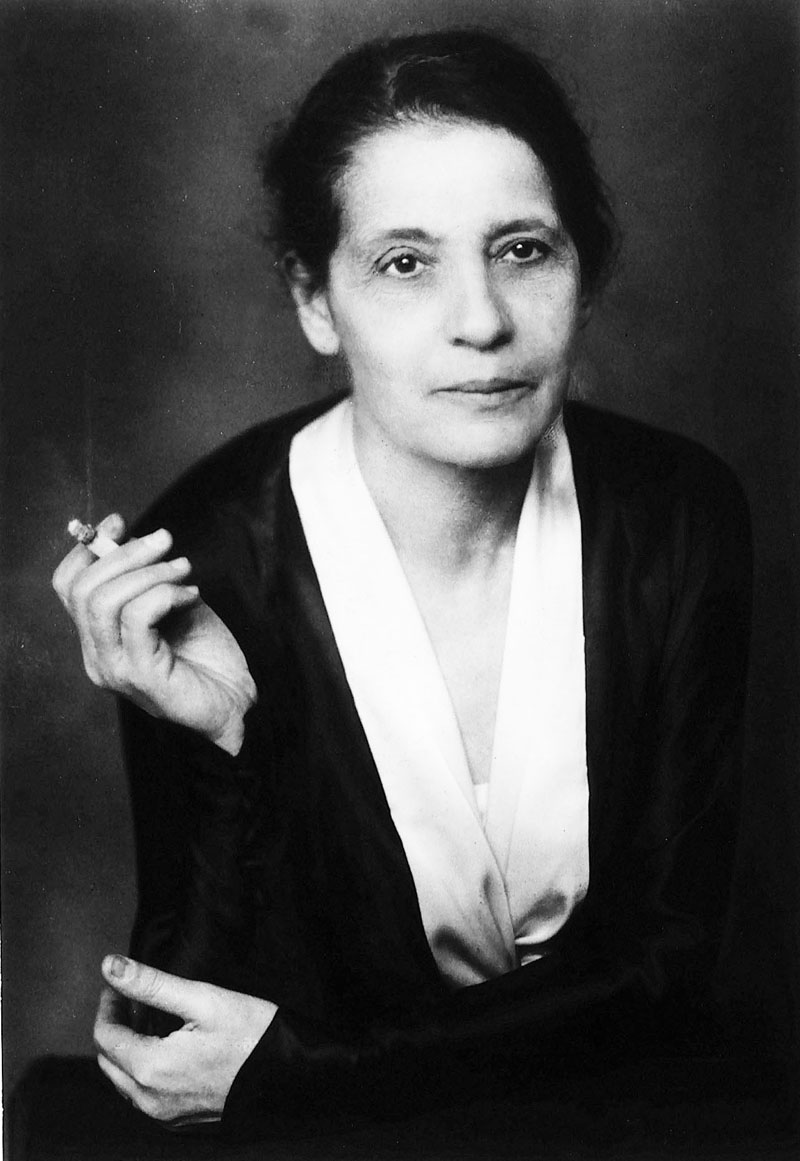

Another woman praised by Einstein as the “German Marie Curie,” Lise Meitner’s story is one of quiet tragedy. Like Emmy Noether, Meitner was born in an era when women were explicitly prohibited from higher learning. Meitner was the second woman ever to earn a degree from the University of Vienna, obtaining a PhD in physics in 1905. Meitner’s father encouraged her ambition, and gave her the money to work in Berlin, where she met physics heavyweight Max Planck.

Planck was notorious for turning away female students, but he begrudgingly allowed Meitner into his lectures. A year later he made her a research assistant to chemist Otto Hahn, with whom she made several groundbreaking discoveries. The Hahn-Meitner team was the Lennon/McCartney of early 20th century nuclear physics, and together they published many articles on radiation and the Auger Effect, which Meitner personally deduced.

After the Nazis took control of Germany in the 1930’s, Meitner’s Jewish lineage became a professional and mortal liability, and she was forced to flee to Holland. Though it was her insights that led to the recognition that nuclear energy was not atomic fusion, but what she termed “fission,” she was forbidden from being granted credit on Hahn’s article. Hahn was granted the Nobel Prize for the discovery in 1944, but Meitner did go on to win several prestigious awards and, like Noether, has a few heavenly objects named in her honor.

5. Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock was studying to be a botanist at Cornell when she took a class in the fledgling field of genetics in 1921. Her professor was so impressed with her work in that class that he invited McClintock to enroll in Cornell’s genetics program, off limits to women at the time. It was at Cornell that she would be introduced to the principal subject of all her major work, maize.

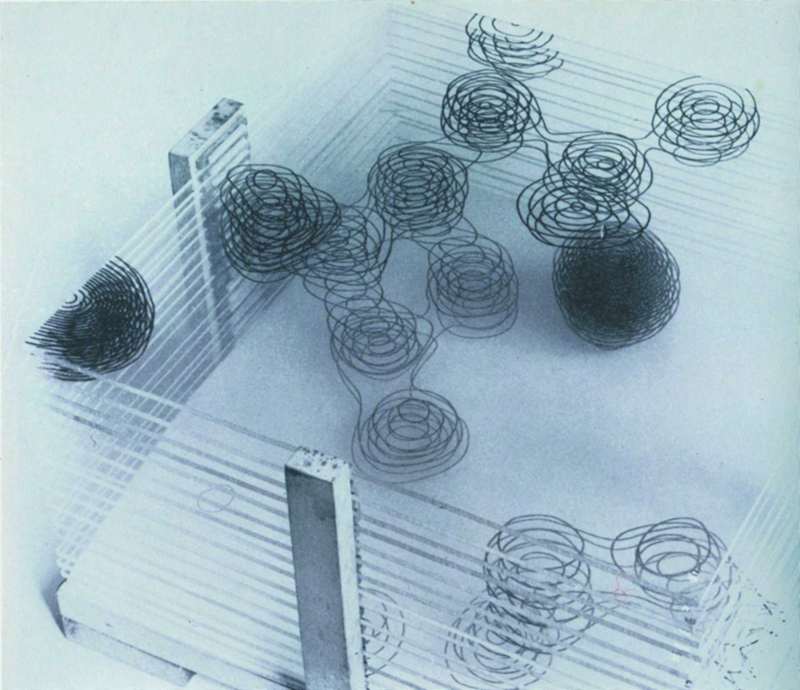

McClintock was concerned with chromosomes, specifically what each pair did, and was able to link certain chromosomes to physiological traits by monitoring the maize’s progeny. She was also integral in determining the role of centromeres in cell reproduction and correctly predicted that telomeres are protective junk information at the ends of all chromosomes.

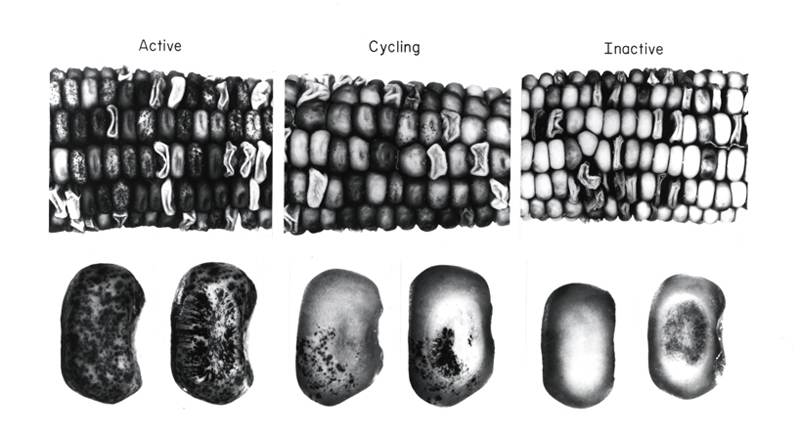

McClintock is most important for her 1948 research into the color patterns of maize kernels. To everyone’s surprise, she discovered that the genetic loci responsible for genetic activation were not only capable of doing more than turn genes off and on, but were actually capable of moving about the chromosome. Her work and conclusions were so ahead of their time that no one understood them enough to give them any attention. It wasn’t until genetics had progressed by a few leaps that she finally earned a Nobel for her work, in 1983.

6. Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Hodgkin was born in Egypt, where she lived with her archaeologist parents. During World War One, Hodgkin returned to England and began her education. Hodgkin displayed a preternatural talent for chemistry early, and was accepted by into Somerville University despite lacking knowledge of Latin. There she became aware of X-Ray crystallography, which would lead to her greatest discoveries.

After successfully structuring a steroid in 1945, she published her findings on penicillin. Nine years later, Hodgkin and her team published their findings on the structure of B12, for which she won the Nobel Prize. She went on to chart the structures of several key organic molecules, helping to determine their function in the body and their artificial creation in a laboratory.